|

You stand upon a cliff, high above the sea, in

a misty grove of silver birch trees. The waves crash and scatter on the rocks

below, an eternal sigh of white noise rising. The grey mist swirls around you,

cutting off familiar sights and sounds. Nothing is as it was. Nothing is as it

seems.

Up ahead and above you in the mist, above the

hole in the stone, The Hag of Birth and Death gazes down upon you. Welcoming

and challenging, silently waiting, she opens the door to

rebirth.

In the shifting realm of

liminal space, she reveals to you the gateway – the vulva of woman –

through which every one of us entered this world,(2) through which all of our foremothers entered this

world. Each one emerging from the one before her, all down the line, open

archway after archway, reaching back through time, like a vaulted corridor

leading directly back to First Woman.(2a)

Wise guardian, who knows these roads so well,

who has trod these paths for countless generations. Oldest ancestor, who gave

birth to us all, whose blood runs through our veins. Her cryptic smile hints at

secret knowledge – She can look every challenge in the face without

flinching; She can meet all changes head-on… and laugh. In your mind you

hear her whisper her name: Síla (“SHEE-luh”).

You bend low and touch the earth, offering a

prayer for guidance as you approach this threshold. Out of the corners of your

eyes you sense the mist swirling; spiral patterns form and dissolve around you,

hinting at mysteries, sparking a distant memory, somewhere beyond your

conscious grasp.

You suddenly notice a heron, Síle na

bPortach (“SHEE-luh nah BORT-uckh”), keeping still, silent vigil

nearby. How long has she been there, watching you? ... You acknowledge her, and

her role as guardian of the gate. You open yourself to her, and you can feel

her looking into you, judging you, deciding whether or not she will let you in.

You open without fear (or despite fear) and join with her stillness. You feel

the silvery-white energy of the birch trees entering you. You breathe in their

purifying, focusing, clean and clearing energy... Opening your heart and

stilling your mind. You chant their ancient name, Beithe (“BAY-huh”).

You feel the powers of land, sky, and sea come together and focus within you.

You take a deep breath, and climb through.

“You had

the calling and died wondering—who is it that calls.

We were all

calling. Down from the centuries beseeching you

to release from stone

unparalleled beauty and in doing so

chipping away the stone encasing

hearts.

…you were called…

you remembered us – the

future…

We were calling you and I am calling you now.”

(3)

It started with the birch

tree…

My personal altar (in a household full of altars)

faces a window, looking out over the trees and the lake. There is a birch tree,

one of many, who lives right on the other side of the glass, her boughs

sweeping into my line of sight whenever I’m at my altar. Sometimes when

I’m sitting there, I’ll open my eyes to see chickadees or catbirds

fluttering in her leaves, or through her branches I’ll see herons wading

in the shallows, or otters splashing and playing out where the waters run deep.

The crows and other wildlife come and go, adding their own emphases and omens

to my rituals. And with the curtains open, as they always are, the rays of the

sun, moon and stars light my work.

On this misty, grey day I was on the other side of

the window – outside on the rocky slope, meditating with this familiar

tree. I was asking her about symbols: What symbol, or goddess, or animal,

works best with the energy of Birch? I had made my offerings of menstrual

blood and breast milk, and I sat waiting, opening, huddled in my cloak in the

shade on this cold morning in early spring.

Suddenly, I received a very strong and clear image

of a Sheela na Gig -type figure. She was sitting in a grove of birch trees,

with her knees drawn up, displaying her signature wide-open vulva, and a huge,

almost maniacal grin on her face. She was laughing.

I have to confess, I was startled. I’m a bit

ashamed to admit it, but the Sheela images had always freaked me out a bit.

Much to my relief, this discomfort was eventually worn away, thanks to

Síla herself, and also because I can’t stand feeling inhibited or

uptight about… well, about much of anything, really. And I certainly

wasn’t going to tolerate feeling squeamish about something related to a

vision or a Goddess image. I mean, I was the one who had started this

dialogue… I had asked for the information, and now it was my job to figure

out what to do with it. I figured I’d better start working with this

Sheela who had popped into my life. After all, I didn’t want to be

rude.

Sheela na Gig - St.

Catherine's Church, Tugford, England.

If you look closely, she's sticking

her tongue out. (!)

Picture courtesy of John Harding and

Megalithica.

Just who is this mysterious figure, the Sheela na

Gig? Is she a representation of the Cailleach – the Hag of Winter, the Old

Woman who lives in the stones? Is she a goddess at all, or rather some

lesser form of otherworldly being? Or were these images merely intended to be

grotesques – carved on medieval churches to shame women about their

bodies, their sexuality, and their power to bring forth life?

When I began looking into

her origins, I encountered this range of questions and opinions among various

polytheists and scholars. At that time, little research had been done on these

images, and even less on the individual being or beings whom they were intended

to represent. (4)

For the moment, I decided

not to worry about these conflicting theories. I felt a deep need to still the

mental voices of the opinions of others and approach her one-to-one, on a

spiritual level. As an experiment, I decided to give her the respect due a

goddess or revered spirit woman, whether she was one or not. I decided to open

to her in the way I would approach a deity, honoured ancestor or nature spirit,

and see what she had to say about it, what she had to show me.

Over the next five years, I experimented with her

(and it seems she experimented with me as well). I did lots of dreamwork and

ceremony;(4a) I invited her in

ritual and prayer, to see if she brought through power, and if so, what kind.

As I got a clearer understanding of her, I became more open to seeing when she

was appropriate to invite into more formal ceremonies – which I learned

largely from noticing when she would simply show up on her own.

She gradually moved into my household. She now

lives over our ancestor altar and our household altar. Surrounded by heron

feathers, cowrie shells, juniper from our garden, and a small forest of twigs

from the silver birch who guards our ritual site, she now dwells on the window

ledge over my personal altar as well – framed by the moving, growing

branches of that same birch tree who seems to have brought us

together.

The Kiltinan Castle Sheela

Photo courtesy of Joe Kenny and

The Fethard Historical

Society - Co. Tipperary, Ireland.

Síla

of the Paradox

“If you hold opposites

together in your mind, you will suspend

your normal thinking process and

allow an intelligence beyond rational

thought to create a new form.”

(5)

In some of the Scottish

lore the year is ruled alternately by the Hag of Winter (the Cailleach) and

the young goddess of Summer (sometimes considered to be the goddess

Brigid).(6) Síla is clearly a

manifestation of the Cailleach as Creator, yet she also embodies a paradox. In

some ways Síla is a third face of this well-known duality: the

manifestation of the usually-hidden doorway that emerges when these forces are

balanced or in flux. She holds the doorway which opens in the liminal-times:

the days of Bealtaine and Samhain, the twilight of sunrise or sunset, and when

the mists arise where the land and the sky meet the waters.(7) She is both and neither, an otherworldly force that

refuses to fit into either/or categories.

She appears when opposing energies meet, and she

is also found when the energies of the Three Realms come together. She opens

and holds the center of sacred space – the doorway which opens when we

connect with the powers of Land, Sky and Sea and balance them within ourselves,

opening to the Spirit that flows throughout and unites all three.

I feel her presence in ceremony, when we enter

that stillness, on the edge between this world and the next. I feel her when I

center, when I still myself and find the quiet place of prayer, the silence

from which the voices of spirits can emerge. I feel her protection, her

guarding of the gateway, when the voices of the spirits get to be too much and

she kindly offers her protection – the calm and stillness in the center of

the whirlwind. As the Storm Hags, the Cailleachan, dance around us, Síla

is the crux point around whom the world spins. She is the silence that enfolds

us, the moment as we poise on the edge before diving into a new realm. Her

shining, silver-white energy washes us clean. She opens our eyes and gives us

the strength and courage to begin anew.

She is the saining smoke rising, the blank paper

waiting, the silence in the singer’s head from which the music is born.

Dance me

through to the stillness

to the point where the motion begins.

Dance me through to the silence

to the edge where the world begins.

(8)

Old Woman of the Stones:

Historical Sheela

In appearance, the Sheela

na Gigs most strongly resemble the Cailleach – our most ancient Celtic

ancestor, the Old Woman, the Winter Hag. Many simplistically refer to her as a

“fertility figure.”(8a)

However, her image combines aspects of fertility and infertility: her

plump vulva, suggestive of youth and sexuality, is stretched wide-open as if in

childbirth, yet in most depictions she has no breasts. In other images, when

she is depicted with breasts they are almost always the drooping, long and flat

breasts of a post-menopausal woman. At times her chest is scarred, with

skeletal ribs, a fierce grimace, and the bald head of either a newborn or an

extremely aged hag. If we take full breasts and bellies to be symbols of

nurturance and material abundance, this is not a nurturing figure. She

seems a creature of paradox and contradiction – representing the primal

extremes of birth and death: the edge-times, the dangerous times.

Stepaside Sheela, Co. Dublin, Ireland.

This Sheela may be guarding the entrance to a crypt.

photo copyright

©2000 Tara McLoughlin.

The earliest known sheela-type images have

generally been believed to have been carved in the late eleventh century, on

medieval churches in south-western France, and then later in England and

Ireland from the twelfth through the sixteenth century. However, these images

from Continental Europe, to my eye, do not much resemble the sheelas of the

Insular Celtic lands, aside from being nude females (or, mostly female. -ish.).

While the Continental images I've seen are more likely to resemble human women,

many of the insular sheelas tend to have the

characteristic flat-topped, large, vaguely triangular head and emphasised eyes

of much older Celtic carvings.(8b)

The Insular sheelas are also much more likely to have the wonderfully weird,

otherworldly, androgynous quality which I explore in this article.

The prevailing opinion

among scholars, at least at the time of the first publication of this article,

was that the sheelas are a Christian invention, and that there was no firm

evidence of sheelas at ancient pagan sites.(9) However, I believe this theory could have been due

to incomplete research; more recently I have become aware of two or three very

old figures on standing stones in Ireland. They are very weathered, but I

believe they could very well be sheelas, or at least precursors to the sheelas.

As far as I'm aware, there has been no official dating

of these first two carvings, though some researchers believe at least one of

them to be pre-Christian. A figure that received a lot of publicity in the

summer of 2003 is most definitely pre-Christian, but we're still determining

whether it is in fact a sheela (I think it is). (9a)

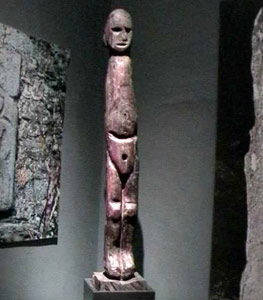

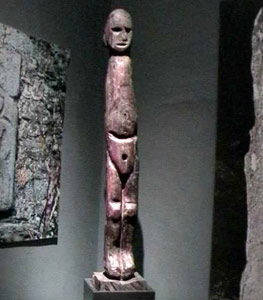

Lusty More figure

copyright ©2004 Shae Clancy

Another fascinating find is the wooden

Ralaghan Figure: “Found in the Ralaghan Bog at

the foot of the Taghart Mountain near Shercock in 1908, this figure is of great

significance as is its find site. It has been radio carbon dated to between

1098 BCE / 906 BCE placing its use towards the end of the Bronze Age. The fact

that the figure was carved of yew was significant as the yew tree was

considered sacred and was believed to have been endowed with regenerative

properties. Taghart Mountain was a hilltop festival site of Lunasa. This site

was used as a place of worship by the late Bronze Age people, by the Iron Age

Celts and into early Medieval times. The Sexuality of the figure is ambiguous.

Quartz grains were found in the pubic hole indicating the possible insertion of

a phallus” - from the info on the museum card. The figure pictured below

is a replica of the original, which is on display in the National Museum of

Ireland in Dublin. While this figure lacks many of the characteristics of the

later, stone sheelas, I believe it could possibly be an early precursor to

those figures. And it makes one wonder what carvings did not survive. That the

carving is of yew is very significant, I believe. In the cycle of the ogham

letters, birch is the first letter (associated with birth) and yew is the last

(associated with death, and with the spirit that survives beyond death). When

we place the letters in a circle, yew and birch are next to each other,

illustrating that death in one world is birth into the next.

Ralaghan

proto-Sheela. photo copyright ©2003 Gay Cannon

So for now, the question of their date of origin

is still open. We may never know for certain, as the oldest-appearing images -

on standing stones in graveyards - have also been heavily worn by exposure to

the elements, while the ones in churches are more likely to have been protected

(if they weren't defaced by human hands, as has happened in all too many

cases). Ultimately, the question of whether the Insular Sheelas are of

“pagan” or “Christian” origin may be irrelevant, as early

Celtic Christianity was not all that different from the Celtic paganism that

preceded it.

Tara Hill Sheela-na-gig, Co. Meath,

Ireland.

photo copyright ©2000 Tara McLoughlin.

When the sheela images began to become widespread

in Irish churches (12th - 16th cent. ce), the Irish people adopted them

enthusiastically, and also began carving them on secular buildings such as

castles and mills. The term “sheela na gig” is said to have been

adopted by folklorists as “simply the common Irish Gaelic expression for

an immodest woman.”(10) The

reason for the adoption of sheelas on secular buildings has been attributed to

the Irish seeing them as a protective force, as noted by nineteenth-century

researchers who “were told by local Irish people that sheelas were

intended to ward off evil.”(11)

This is reported along with a fascinating claim from a traveler in Ireland in

the 1840s that, in order to lift a curse of bad luck, the afflicted should

“persuade a loose woman to expose herself to him.”(!)(12) Here we see the vulva as holding the

power to bless and protect.

A delicious irony in this

history of the sheelas is that, even if they were introduced into the Celtic

lands as a Christian attack on women, “it seems wise to suggest that the

device of the sheela… was absorbed there into a native belief in powerful

female protectors. These carvings upon the later medieval buildings of Ireland

may, then, have been a last manifestation of the old tutelary goddesses.”

(13)

Kilsarkan Sheela, Co. Kerry,

Ireland.

Photo from Tara's Sheela na Gig Page.

In Christian times, She

survived…

Dwelling over church doorways, reminding those

with the ability to see that entering sacred space is to enter the womb of the

goddess – the cauldron of death and rebirth, where we are taken apart and

rebuilt – where we find challenge, dissolution; and then rest, renewal and

change. Reminding people that She is the gateway – we all entered the

world through the womb of a woman. We remained here and grew strong, our

spirits rooting and becoming one with our bodies, through the protection of a

woman: she who in those early days held the life-and-death power of a goddess

over our tiny, fragile forms. No wonder many people find these images

intimidating, frightening, or grotesque.

And She is also the devourer, who takes us back

in at the end of this life – dismembering us, stripping away the

inessentials, until we are pure spirit – transforming us and readying us

for our next turn on the wheel.

When we approach the doorway to sacred space,

or the gateway to life and death, we go with openness and acceptance of the

Mystery: No one truly knows what awaits us on the other side. Will the goddess

who greets you be hideous and challenging? Or will she welcome you with love

and open arms? Are you sure she will even be there at all? And which of these

challenges is truly the hardest for you to face at this point on your

soul’s journey?

The Watergate

Sheela.

Photo courtesy of Joe Kenny and The Fethard Historical Society - Co.

Tipperary, Ireland.

Word Magic:

Etymological Síla

I initially assumed that sheela was

a phonetic spelling of the popular Irish name Síle.(14) But the question remains – if Sheela

(na Gig) was “simply the common Irish Gaelic expression for an

immodest woman,” and even applied to prostitutes, why on earth would

people choose the name for their daughters?(15) I have to wonder: could traits which came to be

described as immodest have earlier been seen as free,

fierce, or bold – traits which were once highly valued in

Celtic cultures before the advent of Christianity? Could this name have been

applied to rebellious, independent women who refused to be limited by

patriarchal laws that treat women as property? What were the origins of this

name? Why did the Irish start calling these images

“Sheela?”

In tracing Irish words

back to their roots, priority is given to the sound of the words, not the

spelling. Many sounds in Irish can only be approximated in English; variant

spellings in the manuscripts are due to different authors’ imperfect

attempts at capturing the sounds of spoken Irish.(16) The spelling variations which follow are all

pronounced basically the same.

Possible meanings to be explored for

Sheela/Síle include: to shelter or shield; the

seed which is planted and the ground in which it grows; offspring,

race or descendants of; raining; an effeminate person; to think, to

consider, to have respect for; and, perhaps my favorite possibility:

cause or origin.

In Scotland, we find the

word sheiling – a shelter, and sheal – to shelter. Both

are derived from the Icelandic root word for shield.(17) These words are a product of the Northern

influence on Gaelic languages and cultures, and meaning certainly fit with the

protective function of the sheelas.

P.W. Joyce gives the root Shee as a

corruption of the Irish Sidh – a fairy hill.(18) While this is probably too

fragmentary to be the sole answer, it is still an interesting and appropriate

association, especially as the mounds can be seen as both the tombs of the dead

and the belly from which new life emerges. While originally only a word for the

mounds, in later usage sidh also came to be applied to any otherworldly

spirit or creature who might be associated with these places.

The Old Irish root word

síl, or siol (both pronounced “sheel”), seems to

be the strongest possibility. It is from this root that we get the rest of the

above-cited words that could be related to Sheela/Síle:

“síl – seed, offspring, race, descendants. silad –

act of disseminating, spreading, to make known. sílaid – either

the seed, etc., which is sown or the earth, etc., which is sown with it;

causes, brings about, produces; generates, multiplies,

spreads.”(19)

It was while digging through

the Early Irish quotations in tiny print under síl and

sílaid that I found something that really made me sit up and take

notice: sila has been used to mean cause or

origin.(20) And it is

pronounced the same as "Sheela" and "Síle." I felt a chill of

recognition. This resonated so strongly with the intuitive impressions I’d

been receiving in my work with her.

Ever since that moment I’ve found myself

thinking of her as Síla (“SHEE-luh”), First

Woman, Eldest of the Ancestors.(21)

This idea of Síla as “the origin” aligns with my sense

of her strong connection to the ancestors, and the tales of the Cailleach as

the mother of many tribes of humans, whose husbands have all died of old age,

one after another.(21a) I have

generally continued to use this variation in the name, both to distinguish her

from the more common personal name, Síle, in reference to the

manuscript where this spelling was found, and to commemorate that sense of

“rightness” that hit me when I found it. However, many prefer to use

the more common spelling, Síle, and I sometimes do as well. In

many ways Síle (Hag) may be the more appropriate variation,

depending on which meaning one is leaning towards.

In some areas of Ireland,

old women have been called Síle.(22) In more contemporary Irish, we also find

Síle defined as “an effeminate person,

sissy”(23) or “a

girlish young man.”(24)

This brings up an interesting connection to the Hag, as Cailleach –

the well-known Gaelic word for hag, old woman, or veiled one

– is also used to refer to “effeminate” men. In the second

definition of Síle, we find the mention of youth. Here we have

twice the paradox: youth and age, and now the suggestion of gender

variance or androgyny. Gender variance is also seen in Sílaid

meaning “the seed and the ground in which it is

planted,” (emphasis mine) and in the gynandrous appearance (no

breasts, no hair) of most of the sheelas.

Gender variance is also

suggested in Fiona Marron’s experience with the Seirkiernan Sheela: when

Fiona touched her, she felt two small holes atop this sheela’s head, much

like those found on some continental Celtic Cernunnos figures that feature

removable horns. Fiona received a strong impression that, for certain

ceremonial purposes, “the stag king’s horns” may have been

placed upon this sheela’s head.(25) This would also parallel the Scottish associations

between the Cailleach and her herds of deer. The

Ralaghan Figure, with its pelvic hole and possible removable phallus, shows

even stronger gynandrous characteristics.

In these situations and others we see a suggestion

of Síla being in between the two polar points of gender, or as

encompassing both. In many ancient (and some contemporary) cultures,

gender-variant people are seen as embodying particularly powerful magic. They

are seen as holding the paradox-energy that lent them special abilities –

usually the power to cross over into unseen realms and to have particularly

strong connections with the Spirits.(26)

The herons and the double spiral

gate.

From a design by George Bain. This version ©1999 kpn

In Irish we also find

Síle na bPortach (“SHEE-luh nah BURT-uckh”)

– the heron.(27) The heron is a

liminal-dweller, living in the misty wetlands of marshes and swamps, and at the

edges of rivers, lakes and oceans. They are sacred creatures who travel in all

three realms: Land, Sea, and Sky. Herons like to nest in tall pine trees, a

sacred tree that is associated with rebirth in the crann ogham.

Portach means bog. Port means place of refuge, haven,

center; fortified place, stronghold.(28) Again, we have themes of protection and a hag who

guards the sacred space.

Herons are often

interchangeable with cranes and storks in Celtic mythology, language and

iconography. The word Corr, usually translated as crane, has been

used interchangeably for these three similar birds.(29) “There are many references to cranes in

Celtic mythology as female guardians of Underworld sacred sites… Cranes

were clearly associated with the world of the dead, and with beings who seemed

to bridge the worlds of the dead and the living with their insight –

particularly old women.”(30)

In European folklore we

find the image of the Stork carrying infants to their birth parents (a tale

which has probably survived due to adults’ discomfort at answering the

children’s question, “Where do babies come from?”). I believe

The Stork could be a surviving reference to the magical role of these liminal

birds: guides and guardians who carry spirits from the Land of the Dead (in

Gaelic mythology found on islands across the western sea), carrying them over

the waters and into this earth-realm, enabling the spirits to

(re-)incarnate.(31)

Gig is much

more obscure, and has been interpreted in a variety of ways by different

researchers. Among many writers, the most commonly-repeated, yet highly

questionable, theory is that the name was originally from one of two possible

Irish phrases, “Sighle na gCíoch(sheela of the

breasts)” or “Síle-ina-Giob (sheela on her

hunkers).” While the construction Sighle na gCíoch is

phonetically somewhat similar to “Sheela na Gig,” we've also seen

that so few of the sheelas actually have breasts. And the few that do... well,

their haggish breasts are really not the most, er, prominent of their

features. While Síle-ina-Giob better fits the physical appearance

of a number of the sheelas, I just don't see the word ina-giob migrating

to the words na gig, in either pronunciation or spelling, during the

time period in question. So I have never found either of these speculations to

be credible. They both seem to me to have been arrived at by the same type of

process I have followed in preparing this article -- an attempt at

reconstructing a meaning in retrospect, rather than discovering a phrase that

was actually gathered in the field during the time periods in question.

(31a)

One theory that is worth consideration is that

Gig could be based on the contemporary Irish and English slang term for

vulva or vagina: Gigh (“Gee” pronounced with a hard

“G” as in the English “go,” but also heard in some areas

with a soft “g,” as in the English “gesture” or the

American “gee whiz”). While this is an obvious candidate, more

research needs to be done to determine how old this term is, and whether it is

of Irish or English origins. 31b

Gig could be related to the Gaelic word

gìog (“geeg”), meaning crouch or to sneak a

peek at.(32) Sheela is crouching

in many of the images, and she is giving people a peek at what is normally

private. Or perhaps it came from the Middle English/Old Norse word gigge

– whirligig or spinning top, from which we get gig – to

reproduce another of the same sort (hmm, parthenogenesis?) and gig

– a small boat.(33) Many

boats are in the shape of a vulva, and this again brings to mind the function

of crossing over – crossing over the waters, whether in physical birth, or

in the spiritual journey to and from the Otherworld islands of the

dead.

Something I believe to

also be worth consideration is Nigheag - another name for the

Washer at the Ford. “Nigheag nan Allt, the washing-nymph of the

streams” is an otherworldly Hag, often connected with the giving and

breaking of geasa, with prophecy and punishment and the granting of wishes.

Because of the Ni sound, and the g being lenited, it wouldn't be

pronouned the same as “na gig”. It sounds more like

“NEE-yuhk.” But visually the two are very similar. As Sile and

Nigheag nan Allt both refer to otherwoldly hags, I think this is a

notable connection.(33a)

I had basically finished

writing this article, and was putting away my reference books. As I picked up

the Gaelic dictionary, it slipped from my hand and literally fell open to:

geug (“gayg”) – a branch, a sapling, a young

female, a nymph.(34) In Irish,

the word is spelled géag (same pronunciation, basically)

and can mean Genealogical branch (of a family tree) or Image of a

girl (made for the May festival).(35) Both words come from the Early Irish word

géc or gég– a branch, a bough, a

respected person.(36) In both

Gaelic and Irish, the genitive form is géige

(“gayg-e”).(36a)

Géag also links Sheela to the

Cailleach and Cailleachan through the early Spring festivals of Là na

Caillich in Scotland, where the celebration is often interchangeable with St.

Patrick's Day; Sheelah's Day, which is observed in Ireland on the day after St.

Pat's; and in Newfoundland, a day known as "Sheilah's brush," also on or around

March 18.(36a1) In Newfoundland,

"Sheila's brush" (or "blush") refers to the "...fierce storm and heavy snowfall

about the eighteenth of March," and she is described as walking the shore in a

long white gown (i.e. of snow). In Ireland, it's said that if it snows on or

around St. Patrick's Day, "Sheila is using her brush" (snow as dandruff!).(36a2) Then just last year (2013) we

discovered an account of a German traveller in Ireland, in 1843, who was told

that "Shilah na Gigh" meant "Sheela with the branch."(36a3)

Again we have a branch or

brush, and the connection to the tales of the Cailleach freezing the earth by

striking it with a stick. Here we have the Hag holding the power to usher in

either winter or spring with her magical branch, not unlike the magical branch

that, in other tales, Otherworldly women use to bring about a change in the

world, such as shifting the human who encounters her into the Otherworld. Here,

the Hag waves her wand and raises the storms that shift us into another season.

In all of these early-spring festivals we see

terminology for the Hag and Hags - Sheelah, Cailleach etc - being used

interchangeably for the being associated with the final blasts of wintery

storms around this time of year, and whose day on March 25th signifies the end

of them (hopefully). And as noted above, there are megalithic alignments in

Ireland, named for the Cailleach, which are oriented to the equinox solar

phenomena.(7)

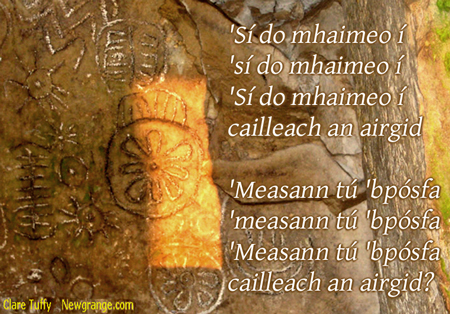

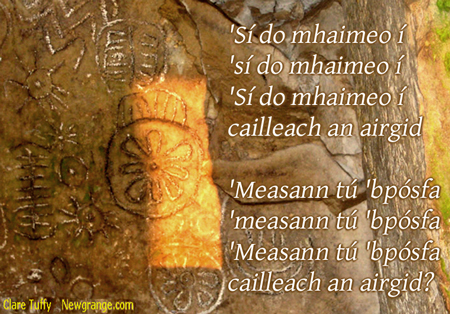

equinox illumination: photo by Clare

Tuffy, text from traditional song added by kpn

In entry #385 of the Carmina Gadelica, we

have an autumn waulking song with the curious line, “But mayest thou sow

them and Géige reap them.”(36b) Could this also show a connection to the harvest

“Maiden” and “Cailleach” customs (“an image of a young

girl, made for festival”), with the Hag as the reaper and/or the corn that

is being harvested? Or be yet another connection to the Nigheag nan Allt as a

death figure? In Gaelic folklore, Géigean (which,

paradoxically, can also be seen as a diminutive form of géige) is

a “wild man” or “gruagach” type figure – depicted as

fierce and hairy, with connections to “death revels,” and the

festival of Samhain.(36c) Some

women in childbed, with no knowledge of Sheelas or Gaelic Hag folklore, have

perceived a Hag spirit accompanied by a heron, connected with birth and death,

who is covered in hair like the wild man figures.(36d) Tapestrys and old drawings depict both male and

female “wild men.” These Gruagach figures are often tricksters in the

folklore and, like the Cailleach, are also associated with herds of deer. In

traditional rhymes and tales, the name of this figure varies, and has been

recorded as Géige, Gìgean, Guaigean, Céigean,

Cìogan, Cìgean, and Cuaigean. Dwelly gives

ceigean as “diminutive and unhandsome person.... clumsily formed

and of low stature.”(36e)

Could the older words for Sheela na Gig have

originally meant something like “Origin of our Branch of the Family,”

“Origin of the People,” “Origin of the Tribe,” “Image

of the Hag-Spirit Who is Also the Spring Maiden” (literally, “Hag of

the Maiden”), or “Wild Hag Trickster Spirit, Who Rules Over Birth and

Death''? Or perhaps any number of variations on these concepts? After all, the

Gaelic mind has always loved puns and multi-leveled meanings.

Síla of the branches,

Origin of the Tribes

Síla of the nymphs, Origins of Womankind;

Eldest of the Ancestors, gynandrous crone and fertile youth,

Hag and

Maiden and in between; seed and ground and truth;

Síla of the

bloodlines, Síla of the trees,

Síla na Géige

Sheela

na Gig

Buckland Sheela - All Saints

Church, Buckinhamshire, England.

Picture courtesy of John Harding and

Megalithica

Ceremonial

Síla

“wise with age and the

androgyny of time”(37)

“the ageless perfect center”(38)

Síla is the Otherworldly gate of Mystery,

The gateway of All Possibility, but also the power to focus – to reach

into the “sea of possibility”(39) and draw something into manifestation in this

world of forms (“seize the possibility”).(40)

My sense is that she controls whether the gate is

open or shut, and that, through aligning with her, she may confer some of this

ability and wisdom upon her allies.

When present in ceremony, the sacred space

Síla creates gives me the distinct feeling of being “between the

worlds” – not yet completely in the Otherworld, and no longer fully

in this world, but in a liminal, charged, basically neutral space from which

one can then choose a direction or destination. Síla seems to specialize

in this liminal zone, the doorway, the center and the edge, where one can pause

and center oneself before fully crossing over. Or she can help build a

protected space in which one can stay and invite other spirits to enter. Some

of this energy and perception, I’m sure, is based on the power of the

birch trees, and how closely I was working with them when I began this

piece.

The Rochester Cathedral

Sheela, Kent, England.

Picture courtesy of John Harding and

Megalithica

Síla of the Trees

Saining with the smoldering

juniper, our prayers rise with the smoke – dancing and

spiraling into

the sky. Bathing ourselves in the scented, energy-filled clouds,

opening

ourselves to the cleansing wind blowing in from the sea.

“Am goeth i

muir” – I am a wind on the sea.

In the Irish ogham lore Birch is associated with

birth, beginnings, cleansing and purification, and the type of healing that

comes from these energies. Cradles were made of birch to keep fragile newborns

safe from unfriendly spirits. An early ogham tale also speaks of birch as a

protector: it was used to protect a woman from being abducted into the

Otherworld.

Like Síla, birch is both a guardian and a

gateway. In my experience, they work together synergistically. Part of

birch’s protection – if she grants it to you – is that she

doesn’t so much banish spirits as set limits and create a

“breathing space” of peace and clarity, from which one can then

choose where to go or who to let in or keep out. The energy of birch and

Síla, like juniper smoke, will clear away bad vibes and create a clean

and sacred space from which to begin your spiritual work.

Birch can also be a

helpful ally for those with mediumistic tendencies. Sometimes the presence of

the spirits can become overwhelming. A reliable method of setting respectful

limits with the spirits is essential. Those dealing with this gift/predicament

need to create firm structure to keep sane – keeping altars for the

spirits and making clear to them that the altar is where they stay, not in your

head. Giving the spirits a defined place to hang out, and working out a

schedule of rituals – regular times for you to check in with them and do

your work together – are ways to prevent them from overwhelming you at

inappropriate times.(40a) And when

you do your spirit work, birch helps to create a safe space within which you

can selectively open.

In my experience this

“protection from spirits” function also extends to dealing with

alcoholism. Birch and Síla have an energy I’ve found helpful to

those in recovery, especially to those in the early stages of getting clean and

sober. Their white, clean, Obatala-type(41) energy can be very stabilizing to those stepping

through the doorway into a new life of sobriety. Síla and birch might

also be helpful in helping people cope with with schizophrenia, though as in

any case of serious mental illness, only as an addition to medication, not as a

replacement.

The Llandrindod Sheela, Powys Mid

Wales

Picture courtesy of John Harding and Megalithica

Síla, Sheela, and

Sacred Space

In the twilight of dawn’s

light

She stirs the mist

From the Edge and the Center

The energy

shifts

(from the edge and the center)

(the world shifts)

I see “sacred space” as having at least

two meanings. First, in the more “mundane” and political sense: The

Earth, our bodies, and all the Earth’s lifeforms are, in one sense or

another, sacred. And second, the way many ceremonial people use the term: A

space that is particularly charged with spiritual forces and the presence of

powerful spirits, and which perhaps contains entrances to the spirit worlds.

Earth is always sacred in the first sense; and she also has sacred sites, which

are sacred in the second sense, whether or not humans ever pray or hold

ceremony there.

So part of what makes sacred space sacred is that

it is energetically and spiritually different from other spaces. It may be

safer, it may be more dangerous, but it deals with different levels of reality

than we access in “ordinary” consensus reality. Though the sacred and

the mundane certainly flow into and inform one another - and are particularly

known to be interwoven in the Gaelic traditions - for those who are sensitive

there has to be some boundary between them. Otherwise, you can lose yourself in

the mist, and you can lose your ability to be fully in either realm. This is a

hazard many spiritually sensitive people deal with, with varying degrees of

success and failure. My work with Síla and birch is one of the more

successful ways I’ve dealt with this challenge.

When my work with Síla first began, I

connected overwhelmingly with her spiritual gateway function and her role in

establishing and protecting sacred space. I was working with her primarily in

ceremony; in deeply altered states of consciousness. At that time, putting

Síla over the doorway to our house would have felt like I was asking

that the entire time I am in this house I should be in an altered, extremely

deepened state, completely focused on communing with the Spirits. I've tried

living that way, and it's not very practical. So for the first few years, she

stayed over the altars.

But after working with her for over twenty years

now, I’ve gotten better at mediating the difference between simply having

a Sheela na Gig image present, and actively asking Síla to open the

gateway. So much so that it's now a subconscious (or at time unconscious) way

of how I am in the world, all the time. Now that I've had some time to

integrate and ground the energies she brought into my life, I've become more

aware, and appreciative of, her more general and “mundane” protective

powers, and how she is the rightful guardian of liminal places like doorways.

Learning to balance the interwoven nature of the spiritual and the physical is

one of the prime challenges and gifts of Gaelic Polytheism, and now that my

life is more fully reflective of that, and that I've had more decades to mature

into that role, her multiplicity of roles makes more sense to me as well. So,

in the tradition of other Gaelic protective charms, like rowan crosses, she not

only lives above the altars here, but a certain sheela now guards the doorway

to our house, as well.

The Holdgate Sheela - Shropshire,

Tugford, England

Picture courtesy of John Harding and Megalithica

In Conclusion

So Who is Sheela/Síla – Goddess,

Grotesque, or Otherworldly Power? Well, these things are not always clear-cut

in Gaelic matters – Powers and Beings can flow, shift, change and have

agendas of their own, and Síla is no exception. The Otherworldly Being

I’ve contacted through my work with Sheela na Gigs and the birch trees,

Whom I call Síla, is a trickster and shapeshifter; she is one of the

sacred Hags (Cailleachan), and probably a face of the Hag herself. She’s a

primal force, older than human speech.

I believe she is our most ancient Gaelic

ancestor, and the closest thing we have to a Creator spirit. Her story can be

found in the tales of the Cailleach, most notably the ones where she creates

the lochs and mountain ranges of Scotland, or guards the gateway to the

Otherworld of the Western Irish Sea. She is also seen in the sovereignty of the

land, and when she herds her deer down by the shore. (42) Her face is seen in the shifting shape of the

land.

In ceremony she arrives as

a distinct energy and presence, who “speaks” through shifting

energies and granting visions, and rarely if ever speaks in any human language.

She is older than human language. Her language is the shifting of the stones,

the sighing in the branches of the trees, the waters crashing on the shore

below the cliffs, the gale howling over the turbulent sea.

When this style proves too vague for our limited

minds, she tends to send more recent ancestors, via vivid dreams, to articulate

the specifics.

Like the many individual and unique sheelas found

throughout the Celtic lands, the face Síla reveals to you may vary

drastically, depending upon the land where she is invited, the situation

regarding the sovereignty of that land, the particular relationship you and

your ancestors have with her, and upon your relationship with the land and the

otherworlds in general.

We have no way of knowing for certain if my

conclusions about Síla resemble the specifics of what our distant

ancestors believed about the carvings. Though the tales of the Cailleach are

solid and unwavering, and live in the Gaelic cultures up to the present day,

not every researcher who has looked into the sheela carvings has concluded they

are votive figures of the Cailleach. For our recent Ancestors, it certainly

seems that many of the sheelas were not initially commisioned as figures of

veneration, and that any spiritual powers and beings that have come to be

attached to these images emerged at a later date – after they took root in

Ireland, and more recently in the more polytheistic pockets of the Celtic

Nations and the diaspora. However, especially given the most ancient carvings,

it is also possible that the earliest sheelas were created by our more

distant, polytheistic ancestors, or that they had images that were so similar

to the sheelas that the two streams of iconography merged. Whichever theory one

believes – whether it's due to their pagan, or despite their Christian,

origins – it seems clear that the images are now Spirit-suffused: that

older spirits, goddesses even, have seen fit to influence the artists and come

through the sheelas – to attach themselves to the images and dwell amongst

us today.

This is simply one spiritual worker's account of

how Síla has manifested in my personal work and among the ever-widening

group of people with whom I’ve shared these ideas and related ceremonies.

One of my reasons for publishing this article, and now maintaining this

website, is to see how others resonate with this information. And, well... She

was getting on my back about putting it out there.

All praises to Síla of

the Paradox:

The boundary, the border,

the edge and the center;

The sunset and sunrise,

She of the sly

grin, She of the wide eyes;

Grimacing crone, Life-giving hag,

the

heron, the crane, and the stork with her bag.

Spinning and laughing,

Paradoxical Crone,

Opener of the Way, Old Woman of the

Stones.

Dancing in dawn’s light

Capering in twilight

Sharply awakening

The Hag of the Stones

Sends rays of light piercing

Clarity burning

Deep in your heart

Deep into your bones

Kathryn Price

NicDhàna

is living by the Hags' Brook in the Northeastern

Forest,

hanging out with the Spirits, listening to the trees,

and

writing it all down.

She serves on the governing councils of

CAORANN and

Gaol Naofa, and can be

reached via her blog

or twitter

The original version of this

article appeared as Síla of the Trees in the “Sacred Spaces,

Sacred Places” issue of Sagewoman Magazine (Winter '98/'99).

It

has been substantially revised and expanded for the

web.

Notes on updates can be found on

the front page.

This

article is copyright ©1998, 2006, 2012, 2014 and may not be reprinted

without the express, written permission of the author.

First revision:

ThornBlossom Moon, 2006

Latest revision: Là na Caillich 2014

|

Footnotes:

(1) Language Note: In this article I have

used the phonetic spelling sheela to indicate the Sheela na Gig

images, and the Early Irish spelling Síla to indicate the

Otherworldly Being or Goddess whom I believe the images may represent. The more

common Irish personal name, Síle, is also a perfectly

correct spelling. All three are pronounced the same. All pronunciations are

approximate – the Celtic languages contain sounds not found in English,

and pronunciation varies regionally. For more on her role as a Creator, see

also page 30 of the

Gaol Naofa Gaelic

Polytheist FAQ.(back)

(2) For those born by C-Section - who exited

their mother's body through the belly, not the vulva - this may be merely

symbolic. Yet note how wide-open the passageway is, and how it goes all the way

up into her belly - even the largest of newborns could fit through that gate.

(back)

(2a)Cydra R. Vaux of

the The Woman Sculpture

Site made a sculpture of my vision. Honour and gratitude to Cydra.

(back)

(3)

Patti Smith,

Early Work (New York: W.W. Norton, 1994), p. 169. (back)

(4) Notable recent exceptions in the US: Lori

DeMarre, “Sheela na Gig (Interview with Irish Artist Fiona Marron),”

The Beltane

Papers Issn 4 (Samhain, 1993), pp. 4-11. Ronald Hutton, The Pagan

Religions of the Ancient British Isles (Oxford, U.K. and Cambridge U.S.:

Blackwell, 1995), pp. 308, 310-15.

¶ (Update, 2/4/00): A caveat

about Hutton - While he was one of the only “scholarly” sources

available in the US when I began this article, I've since realized how

incomplete some of his research is. While his books are generally excellent

studies of history in relation to Neopaganism, his research on sheelas is

superficial at best. He has neglected to mention the sheelas that contradict

his theories. Whether this is due to incomplete research or other factors, I

cannot say. However, I apologize for my former high reccomendation of this

book. I still think it's worth reading as a general work, but in my opinion it

should be approached with the same amount of critical thought with which one

approaches the feminist scholars of whom Hutton is so critical.

¶ On a

much more positive note, thanks to the internet, many scholars are now in touch

with one another and great progress is being made in investigating the sheelas

- they are no longer being totally neglected. See our

Sheela Links

section for some of these fabulous resources. (back)

(4a) Traditional

Gaelic and

Celtic Reconstructionist methods of

opening to vision include

praying

with traditional poetry in the Gaelic languages,

making

offerings to the spirits, listening to the spirits, and other techniques of

fisidecht, such as those practiced by the fili or

fáith. In Gaelic cultures, these visionary abilities are

something one is born with, and usually the person is also born into a family

with a long history of these gifts. While it is possible for people born with

these gifts to learn to better control and utilize them, people who have

inherited these abilities are almost always recognized in childhood or at least

by adolescence. Some who are promoting offensive ideas of "Celtic Shamanism"

have expressed interest in the work I discuss in this article. But when I speak

of visionary and ceremonial work, I am in no way referring to any of the

appropriative neo-shamanic traditions out there, including those who claim to

be Celtic. See the CAORANN site for more on my views of "shamanism."

(back)

(5) Niels Bohr, physicist, quoted in “The

Art of Genius,” The Utne

Reader Issn 8750-0256 (August 1998), p 76. (back)

(6) The Spring Maiden is sometimes considered to

be the goddess Brigid. In much of the Gaelic lore, the year is divided into

halves - Winter: Samhainn to Bealltainn (ruled by

the Hag); and Summer:

Bealltainn to Samhuinn (ruled by the Spring Maiden or Brigid). Samhainn and

Bealltainn are the Scottish Gaelic names for Halloween and May Day. This

duality is also seen in Ireland with the summer ruled by the goddess

Áine (of an ghrian mhór - the large, red sun of

summer), and the winter by her sister Grian (an ghrian bheag -

the small, pale sun of winter).

This video from The Irish Film Board beautifully

illustrates how The Hag renews herself as she renews the land.

(back)

(7) In the pre-Celtic stoneworks of Ireland and

Scotland, there are equinox alignments associated with the Hag, such as at

Loughcrew/Sliabh na Caillí, where both the

spring and fall equinox sunrise illuminates the back of the chamber, which is

covered with symbolic carvings, many of which look to be depictions of the sun.

While the Equinox seems to be the main crux point, The

Day of the Hag can come as early

as March 18, Sheela's Day in Ireland, or April 6, the old date of Là

na Caillich in Scotland. (Also spelled Latha na Cailliche, modern calendar

date, March 25). For many of us the equinox has always felt more like her time,

and putting all this information together has confirmed this. As the Cailleach

is most likely based on a pre-Celtic spirit woman, a Creator spirit native to

the isles of Scotland and Ireland, it makes sense that the equinox, with its

pre-Celtic megalithic alignments, is more her time than the later, Celtic

liminal festivals. (back to "Síla of

the Paradox") (back to "Géag")

(8) From “dance me through,”

darkmoon song cycle ©1989 kpn/katharsis ink. (back)

(8a) “Fertility Figure” usually being

archaeological and anthropological shorthand for “we have no idea.”

Often applied dismissively to any female figurine about which insufficient

research has been done. Or, to paraphrase Judy Grahn, “'Fertility

[Figure]' is one of those generalized terms used to vaguely describe what is

imprecisely understood.” (back)

(8b) Almost any well-illustrated Celtic Art

book with Celtic stonecarvings will illustrate this point, but here are a few

references I've compiled in the Illustration Notes. (back)

(9) The exception being the Pagan sacred sites

where churches were later built and the sheelas carved over their doorways.

However, many who have observed the sheelas in situ have noted that some appear

to be much older, more worn, and sometimes of different stone than the

surrounding structures on which they are mounted. Some believe this could

indicate that the carvings of the sheelas existed before the churches were

built. (back)

(9a) For two Irish sheelas on standing stones,

see

Stepaside Sheela, Co. Dublin and

Tara Hill Sheela-na-gig, Co. Meath. Photographs and

commentary by Tara McLoughlin, on her fabulous

Tara's sheela-na-gig Website.

¶ In the summer of

2003, announcements went out in the media that a “new” figure had

been found that may predate all of these:

Historic stone carving uncovered in Co Fermanagh. However,

it was a figure already fairly well-known, at least to locals and those in

Celtic studies. To those of us looking at the photos, this “carved stone

image, originally from a graveyard on nearby Lusty More Island, [which] has

possible links to the renowned Janus figure at Caldragh Cemetery on Boa Island

” sure looks like a possible in situ sheela to us. The Boa Island figures

are estimated to be around 2,000 to 3,000 years old. These two-faced

“Janus” figures' possible connection to the gatekeeper function also

seems very significant. If you look at the photos, she also has coins and

flowers at her feet - offerings from those who visit her.

¶

Ironically, this “new” find, is in a picture on plate 22 of John

Sharkey's Celtic Mysteries - The ancient religion (New York: Thames and

Hudson, 1975) (back)

(10) Hutton (1995), p.311. Australian slang

usage seems to also support this meaning: as their white population began as a

British prison colony, perhaps the word was imported with Irish prisoners.

(back)

(11) _____, p.314 (back)

(12) Ibid. (back)

(13) Ibid. (back)

(14) Alternate spellings of Síle

include Sheila, sheela and sheelagh. Síle is also used to

translate Julia and Cecilia. (back to "Etymological Sheela") (back to "Géag")

(15) Perhaps to honor St. Cecilia, patron of

music, or St. Julian, patron of travellers and boaters? Actually, the quote,

“simply the common Irish Gaelic expression for an immodest woman”

comes from Hutton (1995), p. 311. As we've had so much trouble finding

any Irish Gaelic meaning for Sheela na Gig, let alone a

“common” one, I have to question Hutton's research here. Sadly, I

wouldn't be surprised to hear he has no Gaeilge. (back)

(16) P.W. Joyce, “Irish Place Names”

in Ronan Coghlan, Ida Grehan, & P.W. Joyce, The Book of Irish Names

(New York: Sterling Publishing, 1989), p.85. (back)

(17) Websters Unabridged Dictionary, 2

vols. (U.S.: William Collins & World Publishing, 1975), pp.1671, 1669.

(back)

(18) P.W. Joyce (1989), p.114. (back)

(19) The Royal Irish Academy, Dictionary of

the Irish Language (Antrim, N.Ireland: Greystone Press, 1990), pp.542-3.

Malcolm MacLennan, A Pronouncing and Etymological Dictionary of the Gaelic

Language (Edinburgh: Acair/Aberdeen University Press, 1991), pp. 299-301.

Niall Ó Dónaill, Foclóir Gaeilge-Béarla

(Éireann: Mount Salus Press, 1992), p.1092. (back)

(20) The Royal Irish Academy (1990), pp.542-3.

See also the online version, eDIL, under both sila and síla.

Whether fadas are used in manuscripts from this time period can be a bit hit

and miss, so we have to take both the accented and unaccented spellings into

account. (back)

(21) When I speak of Síla as the Eldest

of the Ancestors, I’m invoking the oldest Spirit Woman native to the

Insular Celtic lands. I am also including the fada in the spelling as this

gives a clearer representation of the pronunciation, and because I belive it is

probably the original spelling (in transcription errors, it is usually for more

common to find that a fada has been forgotten where needed rather than added

without cause).(back)

(21a) Though this association has not

persisted as strongly as that of her connection with the land, she may have

some ties to the sea as well. In Scotland, the Cailleach herds her deer down by

the sea shore, and in Ireland, the Cliffs of Moher (Ceann Caillí

- Hag's Head) reach out into the Western Sea, across which the dead journey on

their way to the afterlife. I later came across the

The Rochester Sheela na Gig, who holds a fish in each hand

and strongly resembles the Celtic double-tailed mermaids found on standing

stones and manuscripts.

The

Kildare Sheela is in a similar posture, as is

The Glendalough Sheela and the merperson from the Meigle,

Perthshire standing stone in George Bain's “Celtic Art” (New York:

Dover, 1973) p.120, plate V. An image I've seen, said to be of the Norse

Goddess Freya, is also very similar, but I don't know the background or

veractiy of this design (had a link but the page is gone now).(back)

(22) DeMarre (1993), “used to describe old

women in…County Cork.” (back)

(23) Ó Dónaill (1992), p.1092.

(back)

(24) Tomás De Bhaldraithe,

English-Irish Dictionary (Éireann: Criterion Press, 1992), p.

297. See also

Who is Sheila? by Dymphna Lonergan on use of the word to

describe effeminate men in both Ireland and Australia.(back)

(25) DeMarre (1993). Seirkiernan Sheela, County

Offaly, Ireland, 13th-16th cent. C.E. (back)

(26) Judy Grahn, Another Mother Tongue

(Boston: Beacon Press, 1990). Randy Connor, Blossom of Bone (New

York: HarperCollins, 1993). (back)

(27) O’Donail (1992), p.1092.

(back)

(28) ________p. 965. (back)

(29) De Bhaldraithe (1992), pp. 336, 157, 711.

MacLennan (1991), p. 101. (back)

(30) Alexei Kondratiev, “More on Saint

Patrick’s Snakes and Other Irish Critters,” Our Pagan Times

Vol. 4, No. 4 (April, 1994), p. 19. See also: Katharine Briggs, An

Encyclopedia of Fairies (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976), pp. 57-60, on the

Cailleach as a guardian of animals and wells, and how on the Isle of Man, where

She is known as Caillagh ny Groamagh, or the “Old Woman of Gloominess....She

is said to have been seen on St. Bride's day in the form of a gigantic bird

[emphasis mine], carrying sticks in her beak.”(back)

(31) The species of marsh-bird fulfilling this

role seems to vary regionally, depending on which is found on the land in

question. (So, does this mean that in tropical realms Síla’s bird

form is the Pink Flamingo?(!)) (back)

(31a) It is unclear where these two theories

originated. It is likely they were first published by Dr Jørgen Andersen

in his 1977 publication, The Witch on the Wall: Medieval Erotic Sculpture in

the British Isles. Eamonn P. Kelly also mentions them in his 1996

publication, Sheela-na-Gigs: Origins and Functions. I have been very

surprised at how few have been willing to question those guesses.(back)

(31b) For more on this see Gay Cannon's

fabulous site: Ireland's Síle na Gigs. There was also a discussion

on the problems with the theory on

Old-Irish-L.(back)

(32) MacLennan (1991), p.180. (back)

(33) Websters Unabridged Dictionary

(1975), p. 770. (back)

(33a) Alexander Carmichael, Carmina

Gadelica, (Hudson, New York: Lindisfarne Press, 1992), p526. Text notes to

entry #536.(back)

(34) MacLennan (1991), p. 179. (back)

(35) O’Donail (1992), pp. 616-17. Dineen

specifies that géag can refer to "an image of a girl made on Patron day

(Aug. 10) and the May festival. ef. bábog;" - Dinneen, Patrick S.

(Dublin,1927) Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla, p.522. In

other words, "Bábóg na Bealtaine, maighdean an

tSamhraidh..." ~ "Mayday doll, maiden of Summer..." (from

Thugamar Féin An Samhradh Linn).(back)

(36) The Royal Irish Academy (1990), p. 357.

(back)

(36a) The genitive form is the possessive. So,

for example, when coupled with na or nan, it means

“Síla of the branch” or “Origin of

the Tribes” instead of just “Síla branch” or

“Origin Tribes.” In the pronunciation of géige -

“GAYG-uh” or “GAYK-uh” the final “e” should

really be a schwa (but I couldn't figure out how to make one in any of the

available fonts). And depending on dialect and formal vs informal conversation,

the final “e” may or may not be voiced. Na Géige is the

genitive singular. The genitive plural is more commonly written nan

geug, but with a bit of poetic license it could also be written nan

géigean - it's a pun on an obscure word from Cormac's glossary:

“gigean , geigean - master at death revels (Carm.)”

found also in

McBain's online dictionary. With Síla's

“doorway between the world of the living and the world of the dead”

connections, I particularly like this pun, even if most people won't get it.

“Gigean, a dwarf; said too of a naked child.” (MacLennan, p.

180) - The sheelas don't really resemble children, but they are small and

naked. (back)

(36a1) Story, George Morley (Toronto:

University of Toronto Press, 1982)Dictionary of Newfoundland English,

p.469 (Sheelah's Day, March 18, and the appellation of the

"Equinoctical Gales" as "Sheelah's Brush" or "Sheelah's Blush").(back)

(36a2) Loughlin, Annie, (16 March 2013), "Sheelah's

Day," Tairis: A Gaelic Polytheist Blog.(back)

(36a3) Kohl, Johann Georg (Arnoldische

buchhandlung, 1843), Reisen in Irland,

pp.205-8:

"Caecilie mit dem Zweige." As seen above, Cecily or Cecilia

is usually Gaelicised as "Síle," and vice versa. As for "Sheela of the

Branch" being in use in the 1800's... Yeah, I know. I had no idea. I thought I

was the only one who had come to this conclusion. But it's always good to get

confirmation on these things. This is an excellent example of having something

come to us by intuition or spiritual sight (or weird things like dictionaries

leaping off the shelf) and later getting confirmation via older sources.(back)

(36b) Carmichael (1992), p526. Entry #385,

Verses made at the waulking frame: “Thou girl over there, may the

sun be against thee! / Thou hast taken from me my autumn carrot, / My

Michaelmas carrot from my pillow, / My procreant buck from among the goats. //

But if thou hast, it was not without help, / But with the black cunning of the

dun women; / Thou art the little she-goat that lifted the bleaching, / I am the

little gentle cow that gave no milking. // Stone in shoe be thy bed for thee, /

Husk in tooth be thy sleep for thee, / Prickle in eye be thy life for thee, /

Restless watching by night and by day. // May no little slumberer be seen on

thy pillow, / May no eyes be seen upon thy shoulder, / But mayest thou sow them

and Géige reap them, / And Morc garner them to the green

barns!”

¶ For a wealth of info on the Michaelmas and other harvest

traditions, including info on the Cailleach and those grain and carrot rituals,

see: F. Marian McNeill, The Silver Bough - Vol. Two - A Calendar of Scottish

National Festivals - Candlemas to Harvest Home(Glasgow: William MacLellan,

1959).(back)

(36c) Ronald Black (ed), John Gregorson

Campbell's Superstitions of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and

Witchcraft and Second Sight in the Highlands and Islands (Edinburgh:

Birlinn, 2005), p.457. (back)

(36d) Private correspondence and conversations

with author. (back)

(36e) Black (2005), p. 457. (back)

(37) Sheri S. Tepper, Gibbon’s Decline

and Fall (New York: Bantam, 1997), p. 452. (back)

(38) Smith (1994), p. 155. (back)

(39) Patti Smith, “Land,”

Horses (New York: Arista Records, 1975). “I hold the key to the sea

/ of possibilities...”(back)

(40) Ibid. (back)

(40a) Modupue (many thanks) to

Teish for teaching me

this survival skill. (back)

(41) Orisha Obatala is the Yoruba (African)

androgynous Creator Deity of the sky, the white cloth, and the elderly. His/Her

children do not drink alcohol. (back)

(42) For some tales of The Cailleach as

Creator, see the "Theological Questions" section of the

Gaol Naofa

FAQ, this lovely film by The Film Board of Ireland,

An Cailleach Bheara and this article on Wikipedia:

Cailleach. (back)

back to top

|